13 Sep Can These Walls Talk?

by Joanne M. O’Connor

Do Americans have a First Amendment right to express themselves through the custom design of their home, thereby avoiding local regulations that seek to promote community aesthetics? That’s the question a divided panel of the Eleventh Circuit recently addressed—the first federal appellate court to do so—in Donald Burns v. Town of Palm Beach (2021).

Burns’s Custom Beachfront Mansion

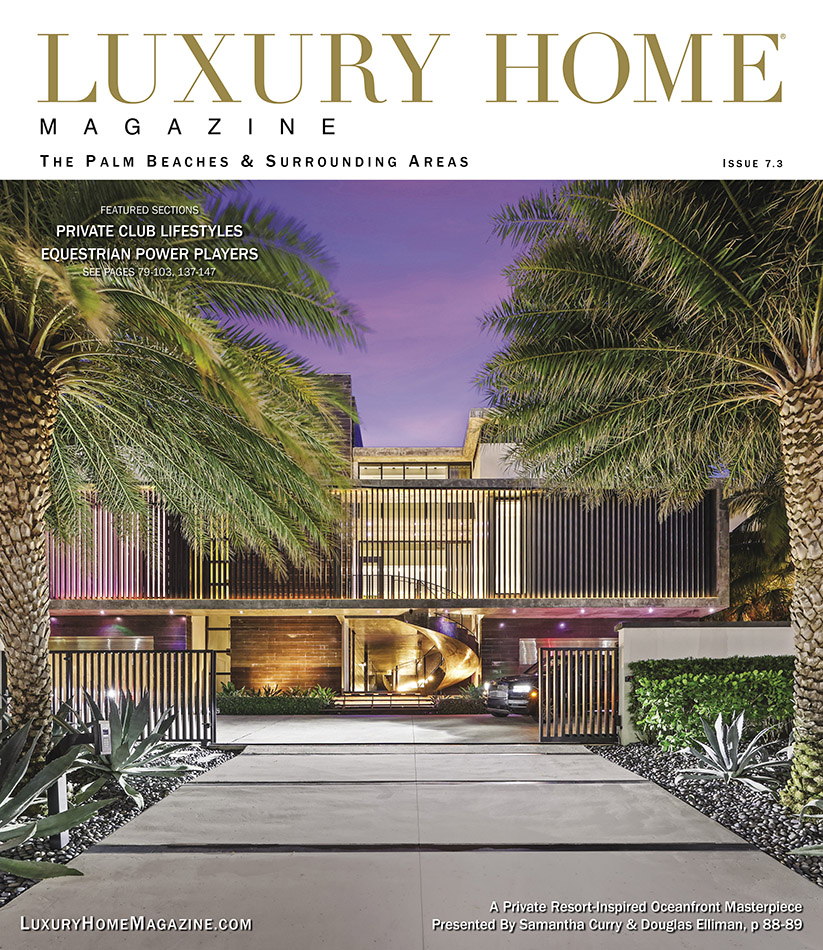

Donald Burns, a resident of Palm Beach and former telecom executive, sought to demolish his 13,000-square-foot Bermuda-style mansion and replace it with a midcentury modern home nearly twice the size. His new two-story oceanfront mansion would have a basement garage, wine storage area and steam room, and would be screened from view by a limestone wall, louvered gate and heavy landscaping.

Palm Beach’s seven-member architectural review commission, experienced in art, architecture and real estate, denied Burns a permit, finding that the proposed residence did not satisfy the town’s “look-alike” ordinance because it was excessively dissimilar from other homes within 200 feet with respect to specified architectural and design criteria.

Burns Sues the Town of Palm Beach

For decades, courts have concluded that the First Amendment protects far more than just the spoken and written word. Based on this principle, Burns sued the Town of Palm Beach in federal court, claiming the town had denied his First Amendment rights to express himself through his residential aesthetic. He complained that the commission had rejected his proposed design based solely on that aesthetic—in other words, simply because they didn’t like midcentury modern-style homes.

During the litigation, Burns asserted that he sought through his design to communicate his “evolved philosophy of simplicity in lifestyle” and the message that he was “unique and different” from his neighbors. He wanted his new mansion “to be a means of communication and expression of the person inside: me.”

The trial court ruled for Palm Beach, albeit finding that the proposed residence did not fall neatly into existing First Amendment case law.

On Appeal, A Split Eleventh Circuit Rules

A sharply divided three-judge panel of the Eleventh Circuit ruled 2-1 against Burns in an opinion that ran more than 130 pages. Writing for the majority, Judge Robert Luck agreed that Burns’s proposed mansion was not expressive conduct but “just a really big beachfront house that can’t be seen, located on a quiet residential street in Palm Beach, Florida.”

The majority held that the plans called for “carefully shielding” most of the home from view—and even if the structure could be seen, there was no evidence a reasonable viewer would understand it to be anything other than “a really big house.”

The majority expressly declined to decide the admittedly “harder issue” of whether residential architecture can ever be expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment and, if so, what is the proper First Amendment test to apply.

In his dissent, Judge Stanley Marcus pointedly criticized his colleagues for curtailing the freedom of expression. Beginning with the premise that architecture is art, he found it difficult to square the majority opinion with well-settled law extending First Amendment protection to artistic expression in all its forms.

Residential architecture is inherently functional and semipermanent. It might be art, but it isn’t pure speech entitled to heightened protection, as even the dissent recognized. Ultimately, Burns’s proposed mansion—20,000-plus square feet shielded by privacy walls, landscaping and the ocean—was far from a perfect vehicle for deciding whether residential architecture can ever be expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment.

Joanne M. O’Connor

A team of women at Jones Foster defended the Town of Palm Beach in Donald Burns v. Town of Palm Beach, a landmark lawsuit brought under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution claiming the right to freedom of expression in residential architecture. That defense team included Litigation Shareholder Joanne M. O’Connor, Litigation Associate Hanna B. Rubin, Paralegal Karen Bould and Litigation Shareholder Margaret L. Cooper (in memoriam). Ms. Cooper argued dispositive motions before the District Court and Ms. O’Connor handled the oral argument before the Eleventh Circuit.

Jones Foster Shareholder Joanne M. O’Connor is a Florida Bar Board Certified specialist in Business Litigation, representing clients in a wide range of complex commercial, real estate, and governmental litigation matters. Ms. O’Connor is experienced in defending actions seeking certification of nationwide and statewide classes and handles jury and non-jury trials and appeals in state and federal courts and before private arbitration panels. Additionally, she serves as an attorney’s fees and professional liability expert witness.

This article originally appeared in the Best Lawyers® “Women in the Law” Business Edition Spring 2023.

505 S. Flagler Dr., Suite 1100

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

(561) 659-3000

jonesfoster.com

You May Also Like…

-

Eastern Accents: Run for the Roses Collection

Gallop off into the sunset with Equestrian pillows for Eastern Accents, our tribute to the elegance ...

24 June, 2025 -

High Point’s Spring 2025 Market

A peek into new and noteworthy products debuting at High Point Spring Market ...

09 June, 2025 -

A Conversation with Julie Roberts, Owner Palm Beach Art Collection

The Palm Beach Art Collection provides collectors with unique - one of a kind - beautiful paintings ...

30 May, 2025